John Kenneth Muir's Reflections on Cult Movies and Classic TV

Creator of the audio drama Enter The House Between. One of the horror genre's "most widely read critics" (Rue Morgue # 68), "an accomplished film journalist" (Comic Buyer's Guide #1535), and the award-winning author of Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002), John Kenneth Muir, presents his blog on film, television and nostalgia, named one of the Top 100 Film Studies Blog on the Net.

Friday, April 26, 2024

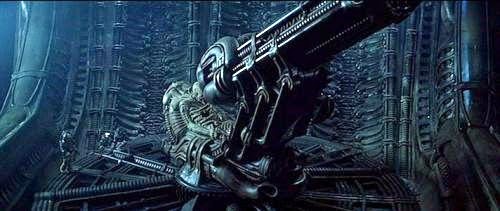

Happy LV 426 Day! The Return of Alien (1979)

award-winning creator of Enter The House Between and author of 32 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of Enter The House Between and author of 32 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Tuesday, April 23, 2024

50 Years Ago: Planet Earth (1974)

Planet Earth (1974) aired fifty years ago today, represents creator Gene Roddenberry's second effort to get his Genesis II (1973) series premise aired on American network television.

As you may or may not remember, Genesis II concerned a 20th century scientist, Dylan Hunt (Alex Cord) awaking in 2133 AD and helping the pacifist organization called PAX (Latin for peace) restore the "best of the past" while ignoring "the worst."

Because of his 20th century knowledge and know-how (and because of a system of sub-shuttles "honeycombing" the post-apocalyptic world...), Dylan proved a perfect "agent" of PAX to accomplish this critical mission of planetary reconstruction (think Irish monks in the Dark Ages...). Still, Dylan Hunt had to overcome his own twentieth century addiction to violence and killing.

One can detect a nearly identical shift at work from Genesis II to Planet Earth. In Genesis II, the brave men and women of PAX lived underground, in dark, depressing and dimly lit caverns. In Planet Earth, PAX folk live above ground, in a shiny, technological metropolis replete with flower gardens and elaborate skyscrapers. Even Dylan Hunt's first voice-over is more upbeat and bright in language, explaining to the audience that in 2133 AD the land is "renewed," and the "air and water are pure again."

In Genesis II, the people of PAX wore simple garments and looked like Roman slaves. In Planet Earth, the people of PAX wear form-fitting and futuristic uniforms that are brightly reminiscent of Star Trek.

In Genesis II, PAX had no advanced technology or advanced medicine. By contrast, Planet Earth reveals a PAX replete with handheld computers, view-screens and large computer banks. The people of PAX are also more knowledgeable here, and there are doctors available who can perform advanced "bioplastic" heart surgery. These changes reveal a completely made-over PAX, one which (like the United Federation of Planets) represents a virtual utopia.

A "recurring" enemy in the form of the barbaric mutants called "The Kreeg" has been added to the mix. These dangerous mutants, like the Klingons of modern day Trek incarnations, boast ridged (or bumpy) foreheads and a style of life geared heavily towards the militaristic. The Kreeg drive around the post-apocalyptic landscape in ancient, souped-up automobiles, and carry twentieth century fire-arms. Basically, It's like Mad Max with Klingons.

Some character relationships have also been tarted up to be as colorful and dynamic as the new environs. The flirtatious relationship between Dylan Hunt (here played by John Saxon) and sexy Harper-Smythe (Janet Margolin) is more pronounced. The other members of Hunt's "Team 21" include the hulking Isiah (Ted Cassidy) and a physician named Baylock (Christopher Cary) who is an "Esper" capable of healing wounds with his mind. Baylock and Isiah share a friendly rivalry that is reminiscent of the Spock/Bones relationship on Star Trek, with Baylock dismissively referring to Isiah as a "savage" when Cassidy's character kneels down in prayer at one point.

Perhaps most significant is the change in Dylan Hunt himself. Saxon's version of the character is a man of action (like James T. Kirk); one who is firmly in command this time around. He barks orders, plots strategy and is a firm, decisive leader, with precious little of the introspection or moodiness of Cord's incarnation. Honestly, John Saxon is a much better lead in this particular role, and his central performance holds Planet Earth together pretty damn well. Like Shatner's Kirk, he is a combination of physical agility/beauty and charming arrogance/swagger.

Another Star Trekkian touch: Dylan Hunt chronicles his adventures on a handheld device. It's not the captain's log, but damn close. Instead, he calls it "a log report to the PAX council."

Given the changes to a punchier, more upbeat tone, philosophy is also played down in Planet Earth. Genesis II ended with the high-minded pacifists of PAX lecturing to Dylan Hunt (who had just saved them all from nuclear annihilation...) about the evils of violence and murder. In Planet Earth, the PAX folk are still peaceful in nature (they continue to use sedative darts as their primary weapons, called PAXer darts, for instance), but they never stop the action to wax philosophic or lecture about pacifism. And judging by the fight sequences here, the people of PAX have also learned the fine art of self-defense.

Directed by the late, great Marc Daniels (who helmed many episodes of Star Trek), Planet Earth (co-written by Juanita Bartlett and Roddenberry and produced by Robert Justman) also features a plot that is easier, in some sense, to identify with. In the opening minutes of the episode, gentle Pater Kimbridge, a leader of PAX, is wounded during a kerfuffle with the Kreeg. Dylan and Team 21 get Kimbridge back to Pax, but they require the skills of a surgeon named John Connor to save the old man's life. Unfortunately, Connor disappeared a year earlier in an "unexplored region" ruled by a matriarchy called "The Confederacy."

There in the confederacy, "males are bought and sold like caged animals." Hunt wonders aloud if is this "women's lib...or women's lib gone mad?" Anyway, he resolves to infiltrate the Confederacy as a slave "owned" (as property) by Harper-Smythe, to locate John Connor and rescue his dying friend. He has just sixty hours to accomplish this task. What Planet Earth establishes with Dylan's mission is the bond of friendship between Kimbridge and Hunt. Hunt states that Kimbridge "is" PAX; both "grace" and "warmth." So underlining the action and weird central scenario in this pilot is a narrative that could have come from Star Trek; about the lengths friends will go to for friends.

Once inside the Confederacy of Ruth, Hunt becomes the property of a dominatrix named Marg (Diana Muldaur), who wins ownership of him in combat with Harper-Smythe. Marg decides she wants him to be a "breeder" (yes!), and Dylan soon learns that all the males here -- called "Dinks" -- are rendered docile by a drug extract in their gruelish food that controls the human "fear/fascination" response. Unfortunately, a side-effect of this drug is sterility. Fewer and fewer children are being born in the Confederacy. The mission is now two-fold for Dylan: set right this topsy-turvy culture (men's lib!) and find the missing Dr. John Connor.

Unfortunately, that's easier said than done. Hunt soon rebels against his new training, and Marg notes that "the human male is an unstable creature." She trains him herself (yippee!), forcing a tied-up Hunt to ingest a full vial of the dangerous extract, rendering him docile. But, in the best teeth-grinding, jaw-clenching tradition of Captain Kirk, Hunt fights the effects of the drug.

Once again, here's a Gene Roddenberry story with a decidedly kinky bent. Dylan Hunt is soon remanded to Marg's home as a "breeder" and once there he promises her that he's, uh...well...good in bed. He claims he has fourteen wives and that his body is attuned to "different practices" than The Mistress might be familiar with. Marg and Hunt share a scene that includes bottles of wine, a bullwhip (whoo-hoo!), and ultimately...a bed. In the sack, Marg and Dylan proceed to discuss the failure of both 20th century men's lib and post-apocalyptic women's lib as governing philosophies, and settle on "people's lib."

Yep, in the words of Dylan Hunt, it's all just a "little non-verbal mutual respect."

Before long, the Kreeg attack the Confederacy, but Dylan has executed a plan to free the Dinks from their drug-induced docility and stand-up and fight. In the end, PAX outsiders, Dinks and Mistresses fight back the violent Kreegs (led by John Quade) and Dylan and Harper-Smythe get Connor back to PAX to save Kimbridge's life.

I hadn't seen Planet Earth in probably fifteen years, and my memory has always been that it wasn't as good; wasn't as "pure" perhaps, as the original, Genesis II. However, on a fresh viewing, I must admit, I actually prefer Planet Earth. John Saxon seems very comfortable and appealing as a leader of men (and women), and he's adept with the romantic and action bits. He's also highly charismatic and appears to be enjoying himself.

And that "light" Star Trek sense of esprit-de-corps and joie-de-vivre is definitely present too, so Saxon understands the style.True, there's less philosophical grandstanding, but the lighter touch is fun and entertaining, and it easily (and humorously) makes points about the timeless "battle of the sexes." Parts of the episode play well as satire; and in toto, Planet Earth is a lot less heavy-handed and grave than Genesis II. This is a planet you wouldn't mind visiting every week.

By making PAX more advanced in Planet Earth, Roddenberry is also better able to compare and contrast various cultures and societies. It's very difficult to be a committed pacifist when you live in desperation (underground in caves; wearing rags); a little easier to do so when some of the basic necessities of life -- like sunlight -- are met. The unisex uniforms also forge a sharp visual distinction between PAX and the other cultures. The character dynamics here also seem more promising, or at least more colorful.

Alas, Planet Earth didn't make the grade either, and never went to series. A third attempt with this formula, also starring John Saxon (this time as Captain Anthony Vico) -- entitled Strange New World (1975) -- was next. Roddenberry had reduced involvement in that pilot, and it too failed to become a series.

award-winning creator of Enter The House Between and author of 32 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of Enter The House Between and author of 32 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Wednesday, April 17, 2024

Enter The House Between picks up Hermes Creative Award (Platinum!) for 2024

Enter The House Between, our audio drama that finished airing its first season in October of 2023, picked up its second award yesterday!

This time, the series won a platinum statue for 2024 in the category of Audio/Radio Program.

The award itself is a Hermes Creative Award, which is sponsored by the Association of Marketing and Creative Professionals.

The Hermes Awards have been around 18 years, and they honor the messengers and creators of the information revolution.

According to the website, "Armed with their imaginations and computers, Hermes winners bring their ideas to life through traditional and digital platforms."

"Each year, competition judges evaluate the creative industry's best publications, branding collateral, websites, videos, and advertising, marketing, and communication programs," and this year, I am proud to say that Enter The House Between was singled out with a Platinum award. (Other categories are Gold, and Honorable Mention).

I want to thank our tremendous cast and crew for making the first season of the series such a memorable one for our listeners.

The second season is in post-production, and you ain't seen (or heard...) nothing yet!

award-winning creator of Enter The House Between and author of 32 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of Enter The House Between and author of 32 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Tuesday, April 16, 2024

90 Years Ago: Tarzan and His Mate (1934)

Tarzan and His Mate (1934) is the finest of the Johnny Weismuller/Maureen O’Sullivan MGM Tarzan movies. It is (shockingly…) frank in its sense of eroticism, and -- for the first time -- brings into sharp focus the franchise’s ongoing central debate or argument about the real nature of white “civilization.”

And so, finally, audiences come to agree with Tarzan’s assessment: they can’t be considered truly civilized. They don’t live in harmony with nature, and they seek to plunder it for some non-existent thing called “wealth.”

Where Tarzan sees Jane as someone he truly loves, Martin Arlington (Paul Cavanaugh), the aforementioned interloper, sees her as another resource of the jungle to use and “own.”

Martin’s safari, with Jane in tow, comes under attack by a tribe of lion men who send man-eaters to kill them. The lions charge and leap, most convincingly, as the white hunters (including Holt and Jane) take refuge on a rock formation. That formation is soon breached, and the scenes of lions battling men (and one woman) look remarkably convincing.

When, another expedition, belonging to a hunter named Van Ness, gets a head-start, Holt and the bankrupt Arlington realize that they need the help of Tarzan (Johnny Weismuller).

They seek out Jane’s (Maureen O’Sullivan) help, hoping she can convince the lord of the jungle to lead them to the graveyard. To convince her to do so, they have brought with them perfume, lipstick, and apparel from England.

Arlington attempts to kill Tarzan, and believes he has succeeded. While Cheetah and other chimps nurse him back to health, Harry and Martin convince Jane to return to England with them.

An injured Tarzan rouses himself for battle, even as Jane, Martin and Holt struggle to fend off the attacking beasts.

Tarzan and His Mate takes a hard turn away from that paradigm and gives the franchise its first fully-formed white villain: Martin Arlington. He won't be the last character of this type in the series, either.

His “shot” involves the theft of the ivory in the elephant graveyard. So though he has lost his fortune, Martin has learned nothing. His agenda is to climb back to the top of the pack, as soon as possible; at least from an economics standpoint.

First, he shoots dead an African worker who refuses an order, making an example of him to others.

Then, he shoots an elephant in the foot, so that it will instinctively lead him to the graveyard.

And finally, he shoots Tarzan so that the jungle man will not stand in his way collecting the ivory.

Arlington believes, then, that this technology gives him the means to control others, and that his designation as “civilized” gives him the right to command and manipulate others.

He thinks, instead, of the elephants, who have the right, he believes, not to have their graveyards desecrated. He also is tender and sweet with Jane upon visiting her father’s grave. Although he is powerful and strong, he is also gentle and caring for others in a way that the so-called “civilized” Martin is not.

Early in the film, the adult Cheetah dies to save Jane from a rhino attack. The ape’s child, young Cheetah, mourns her death, and the film doesn’t whitewash this stark moment. Death is part of life in the jungle. Wickedly, the movie also builds suspense by having the young Cheetah encounter a rhino later. Because of the earlier, emotional encounter, this moment gets viewers to the edge of their seats.

Throughout the film, Jane wears an outfit that leaves her nude from midriff to toes, at least from certain angles.

And there is a delightful and revealing swimming scene here in which Jane swims completely in the nude. This is most unexpected, but the moment reminds one of Adam and Eve in the Garden. In any such comparison, Martin would be the snake, bringing lies and deceit to the couple’s world.

It is natural for Jane and Tarzan to be in love, and to express romantic (sexual) love. Arlington’s ardent desire for Jane looks perverse in comparison. The equation in these films is that Tarzan and the jungle represent a kind of innocence and moral code, and that white civilization interferes with that innocence and moral code.

Tarzan and His Mate is my favorite -- and perhaps the best made -- Tarzan movie in cinema history.

award-winning creator of Enter The House Between and author of 32 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of Enter The House Between and author of 32 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Saturday, April 06, 2024

Return to the Planet of the Apes: (1975) "River of Flames"

award-winning creator of Enter The House Between and author of 32 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of Enter The House Between and author of 32 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Thursday, April 04, 2024

The Subway Game Prologue Now Playing! (Kindle Vella)

award-winning creator of Enter The House Between and author of 32 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of Enter The House Between and author of 32 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Wednesday, April 03, 2024

Guest Post: Lisa Frankenstein (2024)

Lisa Frankenstein Is Made Of More Stale Parts Than Its Creature

By Jonas Schwartz-Owen

The trailer for the new horror comedy Lisa Frankenstein presents a satirical, goofy horror film that melds ’80s fashions and sensibilities with modern meta styles. But the actual film delivers a mirthless slog that offers no new twists, no funny lines, and no tension -- the movie is a major disappointment. Only a sly, unhinged performance by Kathryn Newton is worth recommending.

In the late 1980s, tragic Lisa (Newton, Blockers) must move in with her cold father, hostile stepmother (Carla Gugino, The Haunting of Hill House) and popular, mean-girl stepsister (Liza Soberano) after her mother has been brutally murdered. Practically invisible at her high school, she spends her time at the local cemetery mooning over a grave of an 19th-century boy (Cole Sprouse,Riverdale). When a lightning storm brings him to life, Lisa comforts him and teaches him the modern world. After he starts a killing spree, she sews body parts of his victims to make him a “real boy.”

Written by Oscar winner Diablo Cody (Juno, as well as the cult horror/comedy Jennifer’s Body), Lisa Frankenstein has elements that could make for broad parody, but the script does a lazy job, following the predictable path without rewarding the audience with anything surprising. We’ve seen so many fish-out-of-water movies, as well as ugly-duckling-turns-into-a-psychopathic-swan movies, that this film really needs to raise the bar, but the bar remains firmly planted at ground level.

This is the feature directorial debut of Zelda Williams (the late, great Robin’s daughter), and her pacing and stylizations could have used some of the zaniness that made her father a genius. She does film one black & white fantasy sequence early in the movie that evokes the music videos of ’80s New Wave artists Siouxsie And The Banshees, but for the most part, this film could have been shot for television.

Newton, who was delightfully insane as both a wallflower high school student and a gleeful serial killer in the imaginative horror/comedy Freaky, once again shines, especially when her character embraces a goth look and blasé attitude. Her silent stares at other characters lift the character from the flatness of the page. Sprouse appears to have studied hard to perfect the walk (or rather, the stiff drag) of a dead creature, but he’s not really given much character. Gugino, who stole the Netflix series Fall of the House of Usher from all her talented co-stars, could have had fun with her evil stepmom role, but the performance also felt rote and perfunctory.

Lisa Frankenstein feels forced the entire time, like a monster trying to fit into the modern world. I don’t expect even angry villagers to care enough to chase this monster down. For a better spoof of the ’80s and horror, catch Totally Killer on Amazon starring Kiernan Shipka (Chilling Adventures of Sabrina) as a time-traveler tracking down her mother’s murderer. Everything missing here in Lisa Frankenstein – thrills, laughs, surprises – are given out freely in Totally Killer like Halloween candy at the cool neighbor’s house.

award-winning creator of Enter The House Between and author of 32 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

award-winning creator of Enter The House Between and author of 32 books including Horror Films FAQ (2013), Horror Films of the 1990s (2011), Horror Films of the 1980s (2007), TV Year (2007), The Rock and Roll Film Encyclopedia (2007), Mercy in Her Eyes: The Films of Mira Nair (2006),, Best in Show: The Films of Christopher Guest and Company (2004), The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi (2004), An Askew View: The Films of Kevin Smith (2002), The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film & Television (2004), Exploring Space:1999 (1997), An Analytical Guide to TV's Battlestar Galactica (1998), Terror Television (2001), Space:1999 - The Forsaken (2003) and Horror Films of the 1970s (2002).

Happy LV 426 Day! The Return of Alien (1979)

It is quite difficult to believe, but in 2024, Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) turns 45 years old. Perhaps the most amazing thing about Alie...

-

My friend, Johnny Byrne (27 November 1935 – 3 April 2008) -- an Irish poet, philosopher and writer on science fiction TV series such as Sp...

-

Today, we return to the blog's ongoing survey of the fantasy films of the 1980s. Last week, we remembered the visually-impre...

.jpg)